She’s one of the last of Hollywood’s golden-age stars—the girl who stole Humphrey Bogart’s heart at age 19 and has been grappling with their dual legend ever since. Now 86, Lauren Bacall looks back on a lucky, if often difficult, life as she gives it straight to Matt Tyrnauer, talking about the effect of Bogie’s fame on her and their kids; her very brief engagement to Frank Sinatra; her stormy second union, to Jason Robards; and why she hates the Oscar she received, in 2009.

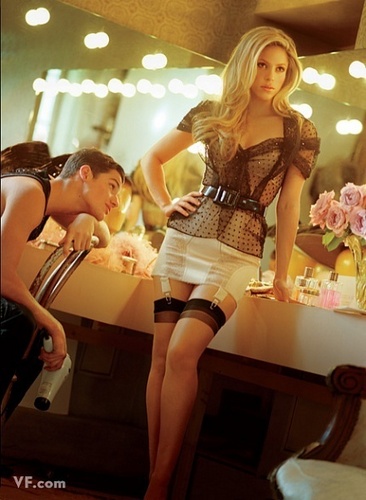

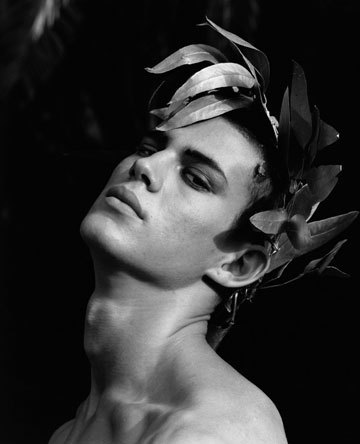

By Matt Tyrnauer•Photograph by Annie Leibovitz•Styled by Jessica Diehl

March 2011

The apartment is cavernous, on a high floor of the Dakota, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Huge windows overlook Central Park, 30 feet above the tree line, with the grand residential buildings of Fifth Avenue in the distance. My meetings with Lauren Bacall, who is 86, are at three P.M. in the winter, so the light is silvery blue in the wood-trimmed parlor, where Bacall has set the scene for our sessions. A tall wooden chair, for her, is positioned in the center of the room, near a low, white-and-green-upholstered club chair, for me. A single lamp burns in a distant corner. She is dressed, every time, in a black shirt, black pants, and black orthopedic shoes. She always has with her Sophie, an excitable papillon, and what she refers to as “my friend,” her aluminum walker, with tennis balls on its feet. The “fucking fracture that I’ve got on the hip” is the result of a bathroom fall a few months back, a frustrating how-do-you-do after a life of near-perfect health. “Can you imagine? It’s the only time I have been in the hospital except for the times when I gave birth,” she says. A fighter by nature, Bacall has begun to venture out, supported by her walker, onto 72nd Street, going alone to physical therapy, for the most part unrecognized, just another senior citizen. “People don’t pay any attention to me or the walker,” she says. “The other night I was going into a doctor’s office, and some son of a bitch came out of the building, almost knocked me over. I said, ‘You’re a fucking ape!’—screaming at him. He never even turned around. Couldn’t care less, this big horse of a man.”

She hands me a box of Bissinger’s chocolate bark and instructs me to tear off the cellophane. “This is going to be our snack,” she says, explaining that she is the St. Louis-based chocolate company’s spokesperson. “I just said ‘Bissinger’s is the best chocolate’ into a microphone when I was in St. Louis touring with Applause [the Broadway musical, in 1971], and every year the boxes of chocolate keep coming, so I guess I am still their spokesman.” The cellophane is hard to puncture, and she suddenly snaps, “What’s taking you so long to open that box? Get over here and sit down!”

“Patience,” Bacall wrote in her memoir, By Myself (1978), “was not my strong point.”

“There have always been rumors about me: Oh, she’s very difficult. Be careful of her. People who don’t know me—even some people who do know me—know that I say what I think. Very few people want to hear the truth. Bogie was like that, my mother was like that, and I’m like that. I believe in the truth, and I believe in saying what you think. Why not? Do you have to go around whispering all the time or playing a game with people? I just don’t believe in that. So I’m not the most adored person on the face of the earth. You have to know this. There are a lot of people who don’t like me at all, I’m very sure of that. But I wasn’t put on earth to be liked. I have my own reasons for being and my own sense of what is important and what isn’t, and I’m not going to change that.”

There is a pause as I make a note on this aria.

“Uh-oh, he’s thinking too much,” she says. “You are going to cut me to ribbons, I can tell. What’s the argument for this story? That I am still breathing? I don’t talk about the past,” she proclaims, taking a piece of Bissinger’s and pushing the rest in my direction. Nevertheless, the past is present everywhere in this room and all over the apartment. It is, in fact, never far from her thoughts. She has lived in great comfort in this place since 1961, when she bought it for $48,000. “I called my business manager in California and said, ‘Sell all of my stock’—what little of it I had—and it’s the only smart financial move I ever made,” she says. The north wall of the parlor, which she faces, is a map of memories in the form of framed photos, drawings, and ephemera, testifying to the fact that she knew the greats from a tender age. “It’s not about me. It’s about all the people who were my friends,” she says. The centerpiece is a vermilion portrait of her as the character Schatze in How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) by that film’s director, Jean Negulesco. She was at the height of her beauty then.

“My son tells me, ‘Do you realize you are the last one? The last person who was an eyewitness to the golden age?’ Young people, even in Hollywood, ask me, ‘Were you really married to Humphrey Bogart?’ ‘Well, yes, I think I was,’ I reply. You realize yourself when you start reflecting—because I don’t live in the past, although your past is so much a part of what you are—that you can’t ignore it. But I don’t look at scrapbooks. I could show you some, but I’d have to climb ladders, and I can’t climb.”

The Prettiest Usher

‘Bogie was 25 years my senior,” she begins. They were married on May 21, 1945, when she was 20 and he was 45, at Malabar Farm, in Lucas, Ohio, the home of Bogart’s great friend the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Louis Bromfield. Bogart liked to refer to himself as “a last-century boy,” having been born in 1899. “I fairly often have thought how lucky I was,” she tells me. “I knew everybody because I was married to Bogie, and that 25-year difference was the most fantastic thing for me to have in my life.” She points to the wall—to signed photos of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, Robert Benchley, Clifton Webb, Noël Coward, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Lionel Barrymore, John Gielgud, and Truman Capote—and says with a sigh, “It’s like all the talent’s gone. It’s very sad.

“Bogie started in the theater not as an actor but as a stage manager, and he got on the stage by accident, because one of the actors did not show up for a performance one evening, so he went on for him. And he said, ‘O.K., this isn’t too bad.’ I don’t know why he ended up in California, because he was brought up in New York. His mother was an artist, Maud Humphrey. His father was a doctor, Belmont DeForest Bogart. How do you like that for a name? He was Humphrey DeForest Bogart.”

There may be some mystery as to how Bogart ended up in Hollywood, but how Lauren Bacall got there, 67 years ago, from her native New York is the stuff of legend.

She was born Betty Joan Perske, in the Bronx, on September 16, 1924. Her mother and mother’s mother were Jewish immigrants from Romania. Her father, William Perske, abusive and unfaithful, fled when Betty was six. She took her grandmother’s name, Bacal, at age eight, eventually adding the second l to make it easier to pronounce. The family’s finances were always shaky. Bacall’s mother worked multiple jobs to support her only child. Betty’s dream from her very early years was to be an actress, specifically the second coming of Bette Davis, whom she worshipped, imitated, and literally stalked when Davis was in New York in the early 40s, staying at the Gotham Hotel, off Fifth Avenue.

While a student at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, in Manhattan, Bacall relentlessly pursued a theatrical break: barging into the office of Broadway producer Max Gordon and begging for a part, striking up a friendship with the actor Paul Lukas, selling the casting tip sheet Actor’s Cue outside Sardi’s, going on an age-inappropriate date with the notoriously lecherous star Burgess Meredith, whom she had met while volunteering at the Stage Door Canteen. (Bogart always believed that Meredith had taken her virginity and later confronted him about it. Meredith and Bacall denied it, but, she says, “Bogie didn’t believe him.”) During this period she was also an usher at the St. James Theatre, and she got the first augury of immortality—if you don’t count being crowned Miss Greenwich Village 1942—when the theater critic George Jean Nathan gave her a glowing notice. As she recalled in By Myself:

Every year he wrote a page in Esquire appraising the past theatre season and listing merits and demerits. On the merit side of the July 1942 issue was the following: “The prettiest theatre usher—the tall slender blonde in the St. James’ Theatre, right aisle, during the Gilbert & Sullivan engagement—by general rapt agreement among the critics, but the bums are too dignified to admit it.” I really enjoyed that one. Being noticed by someone renowned in theatrical circles—anyone—was something. It wouldn’t get me a part, but it couldn’t hurt and it was better than just disappearing.

The day after her 18th birthday, Bacall made her stage debut in a George S. Kaufman play, Franklin Street, which closed after its Washington, D.C., tryout. However, the smoldering good looks that had caught Nathan’s eye landed her in front of Diana Vreeland, then the fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar, for a model casting. She made the cover in March 1943, and that photo of her, standing in front of a Red Cross office door, caught the attention of Nancy “Slim” Hawks, then the wife of movie director Howard Hawks, who suggested to him that he give Bacall a screen test.

By Matt Tyrnauer•Photograph by Annie Leibovitz•Styled by Jessica Diehl

March 2011

The apartment is cavernous, on a high floor of the Dakota, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Huge windows overlook Central Park, 30 feet above the tree line, with the grand residential buildings of Fifth Avenue in the distance. My meetings with Lauren Bacall, who is 86, are at three P.M. in the winter, so the light is silvery blue in the wood-trimmed parlor, where Bacall has set the scene for our sessions. A tall wooden chair, for her, is positioned in the center of the room, near a low, white-and-green-upholstered club chair, for me. A single lamp burns in a distant corner. She is dressed, every time, in a black shirt, black pants, and black orthopedic shoes. She always has with her Sophie, an excitable papillon, and what she refers to as “my friend,” her aluminum walker, with tennis balls on its feet. The “fucking fracture that I’ve got on the hip” is the result of a bathroom fall a few months back, a frustrating how-do-you-do after a life of near-perfect health. “Can you imagine? It’s the only time I have been in the hospital except for the times when I gave birth,” she says. A fighter by nature, Bacall has begun to venture out, supported by her walker, onto 72nd Street, going alone to physical therapy, for the most part unrecognized, just another senior citizen. “People don’t pay any attention to me or the walker,” she says. “The other night I was going into a doctor’s office, and some son of a bitch came out of the building, almost knocked me over. I said, ‘You’re a fucking ape!’—screaming at him. He never even turned around. Couldn’t care less, this big horse of a man.”

She hands me a box of Bissinger’s chocolate bark and instructs me to tear off the cellophane. “This is going to be our snack,” she says, explaining that she is the St. Louis-based chocolate company’s spokesperson. “I just said ‘Bissinger’s is the best chocolate’ into a microphone when I was in St. Louis touring with Applause [the Broadway musical, in 1971], and every year the boxes of chocolate keep coming, so I guess I am still their spokesman.” The cellophane is hard to puncture, and she suddenly snaps, “What’s taking you so long to open that box? Get over here and sit down!”

“Patience,” Bacall wrote in her memoir, By Myself (1978), “was not my strong point.”

“There have always been rumors about me: Oh, she’s very difficult. Be careful of her. People who don’t know me—even some people who do know me—know that I say what I think. Very few people want to hear the truth. Bogie was like that, my mother was like that, and I’m like that. I believe in the truth, and I believe in saying what you think. Why not? Do you have to go around whispering all the time or playing a game with people? I just don’t believe in that. So I’m not the most adored person on the face of the earth. You have to know this. There are a lot of people who don’t like me at all, I’m very sure of that. But I wasn’t put on earth to be liked. I have my own reasons for being and my own sense of what is important and what isn’t, and I’m not going to change that.”

There is a pause as I make a note on this aria.

“Uh-oh, he’s thinking too much,” she says. “You are going to cut me to ribbons, I can tell. What’s the argument for this story? That I am still breathing? I don’t talk about the past,” she proclaims, taking a piece of Bissinger’s and pushing the rest in my direction. Nevertheless, the past is present everywhere in this room and all over the apartment. It is, in fact, never far from her thoughts. She has lived in great comfort in this place since 1961, when she bought it for $48,000. “I called my business manager in California and said, ‘Sell all of my stock’—what little of it I had—and it’s the only smart financial move I ever made,” she says. The north wall of the parlor, which she faces, is a map of memories in the form of framed photos, drawings, and ephemera, testifying to the fact that she knew the greats from a tender age. “It’s not about me. It’s about all the people who were my friends,” she says. The centerpiece is a vermilion portrait of her as the character Schatze in How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) by that film’s director, Jean Negulesco. She was at the height of her beauty then.

“My son tells me, ‘Do you realize you are the last one? The last person who was an eyewitness to the golden age?’ Young people, even in Hollywood, ask me, ‘Were you really married to Humphrey Bogart?’ ‘Well, yes, I think I was,’ I reply. You realize yourself when you start reflecting—because I don’t live in the past, although your past is so much a part of what you are—that you can’t ignore it. But I don’t look at scrapbooks. I could show you some, but I’d have to climb ladders, and I can’t climb.”

The Prettiest Usher

‘Bogie was 25 years my senior,” she begins. They were married on May 21, 1945, when she was 20 and he was 45, at Malabar Farm, in Lucas, Ohio, the home of Bogart’s great friend the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Louis Bromfield. Bogart liked to refer to himself as “a last-century boy,” having been born in 1899. “I fairly often have thought how lucky I was,” she tells me. “I knew everybody because I was married to Bogie, and that 25-year difference was the most fantastic thing for me to have in my life.” She points to the wall—to signed photos of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, Robert Benchley, Clifton Webb, Noël Coward, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Lionel Barrymore, John Gielgud, and Truman Capote—and says with a sigh, “It’s like all the talent’s gone. It’s very sad.

“Bogie started in the theater not as an actor but as a stage manager, and he got on the stage by accident, because one of the actors did not show up for a performance one evening, so he went on for him. And he said, ‘O.K., this isn’t too bad.’ I don’t know why he ended up in California, because he was brought up in New York. His mother was an artist, Maud Humphrey. His father was a doctor, Belmont DeForest Bogart. How do you like that for a name? He was Humphrey DeForest Bogart.”

There may be some mystery as to how Bogart ended up in Hollywood, but how Lauren Bacall got there, 67 years ago, from her native New York is the stuff of legend.

She was born Betty Joan Perske, in the Bronx, on September 16, 1924. Her mother and mother’s mother were Jewish immigrants from Romania. Her father, William Perske, abusive and unfaithful, fled when Betty was six. She took her grandmother’s name, Bacal, at age eight, eventually adding the second l to make it easier to pronounce. The family’s finances were always shaky. Bacall’s mother worked multiple jobs to support her only child. Betty’s dream from her very early years was to be an actress, specifically the second coming of Bette Davis, whom she worshipped, imitated, and literally stalked when Davis was in New York in the early 40s, staying at the Gotham Hotel, off Fifth Avenue.

While a student at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, in Manhattan, Bacall relentlessly pursued a theatrical break: barging into the office of Broadway producer Max Gordon and begging for a part, striking up a friendship with the actor Paul Lukas, selling the casting tip sheet Actor’s Cue outside Sardi’s, going on an age-inappropriate date with the notoriously lecherous star Burgess Meredith, whom she had met while volunteering at the Stage Door Canteen. (Bogart always believed that Meredith had taken her virginity and later confronted him about it. Meredith and Bacall denied it, but, she says, “Bogie didn’t believe him.”) During this period she was also an usher at the St. James Theatre, and she got the first augury of immortality—if you don’t count being crowned Miss Greenwich Village 1942—when the theater critic George Jean Nathan gave her a glowing notice. As she recalled in By Myself:

Every year he wrote a page in Esquire appraising the past theatre season and listing merits and demerits. On the merit side of the July 1942 issue was the following: “The prettiest theatre usher—the tall slender blonde in the St. James’ Theatre, right aisle, during the Gilbert & Sullivan engagement—by general rapt agreement among the critics, but the bums are too dignified to admit it.” I really enjoyed that one. Being noticed by someone renowned in theatrical circles—anyone—was something. It wouldn’t get me a part, but it couldn’t hurt and it was better than just disappearing.

The day after her 18th birthday, Bacall made her stage debut in a George S. Kaufman play, Franklin Street, which closed after its Washington, D.C., tryout. However, the smoldering good looks that had caught Nathan’s eye landed her in front of Diana Vreeland, then the fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar, for a model casting. She made the cover in March 1943, and that photo of her, standing in front of a Red Cross office door, caught the attention of Nancy “Slim” Hawks, then the wife of movie director Howard Hawks, who suggested to him that he give Bacall a screen test.